Why do you document?

In classrooms that use inquiry-based approaches – including those who use Emergent Curriculum, engage in long or short term project work, or are inspired by Reggio Emilia – we work hard to find the time to document children’s ideas, thinking, and learning. It’s not easy to find the time and mental energy to do this in a packed classroom day or week!

The phrase ‘making learning visible’ has been in use for some time now (and is borrowed from the book of the same title, from Project Zero). I wonder….is that the only reason we document? Have we all asked ourselves the question ‘Why am I documenting?’ Perhaps documentation is required by your organization; nevertheless, it’s still a question worth asking, because the reason that we document – whatever that may be – will change the very nature of the documentation and its possible uses.

When our intent is to ‘make learning visible’ we have to ask ourselves ‘visible to whom’? If the documentation is geared toward parents, the language may change a little in order that diverse readers will find the content accessible. What exactly is it that we want parents to understand about what the children are doing? How are we seeing the children through a ‘co-researcher’ teacher lens, which might differ and be puzzling to a parent/caregiver? How can we make co-construction of knowlege with children visible to parents? What else might we need to clarify? The tone and voice of the documentation does not need to be didactic, but should give a sense of our philosophy through photos and text about action, process, discovery, and why this is meaningful. A word of warning here! ‘Meaning’ (and making it visible to others) involves much more than a developmental statement such as ‘the children improved their language skills by…..’ Perhaps we can try to explain, instead, why the event is exciting to us, puzzling, astonishing, or provides a moment of recognition of the child’s deep thinking. Let’s try to share those wonderful moments of recognition that touch our hearts and minds.

If geared toward colleagues, either in our own setting or in our wider Community of Practice, the content and language might be entirely different….perhaps including not only the children’s ideas and thinking, but also the teachers’ thinking and questions. We don’t understand everything that children do and say in our classrooms, and documentation with and for colleagues is a valuable way of reflecting upon and researching the answers to those questions. Even ‘raw’ documention (ie those photographs and notes that haven’t been assembled yet), when shared and discussed with others, can be a valuable form of thinking with others – a provocation for us as teachers to think deeply about what was going on, and what questions arise for us out of the children’s actions and words. These arising questions are SO important in terms of putting us in the role of researcher. How are we going to find the answers through our daily practice? What decisions must be made in response to our questions? In our documentation study group here in Halifax, N.S. we find that sharing our documentation leads to huge discussions and big questions around ever-widening topics. It expands our perspectives and thinking, often taking us to places that are completely unexpected. For instance, when looking at a photo of superhero play, we might diverge into discussions around culture, environment, society’s view of the superhero, an examination of our discomfort with some types of play and what that might mean, and so on. Far from being ‘off topic’ in terms of this particular piece of documentation, this kind of discussion leads to deeper and wider thinking – some of which might end up in the final documentation in the form of thought-provoking questions.

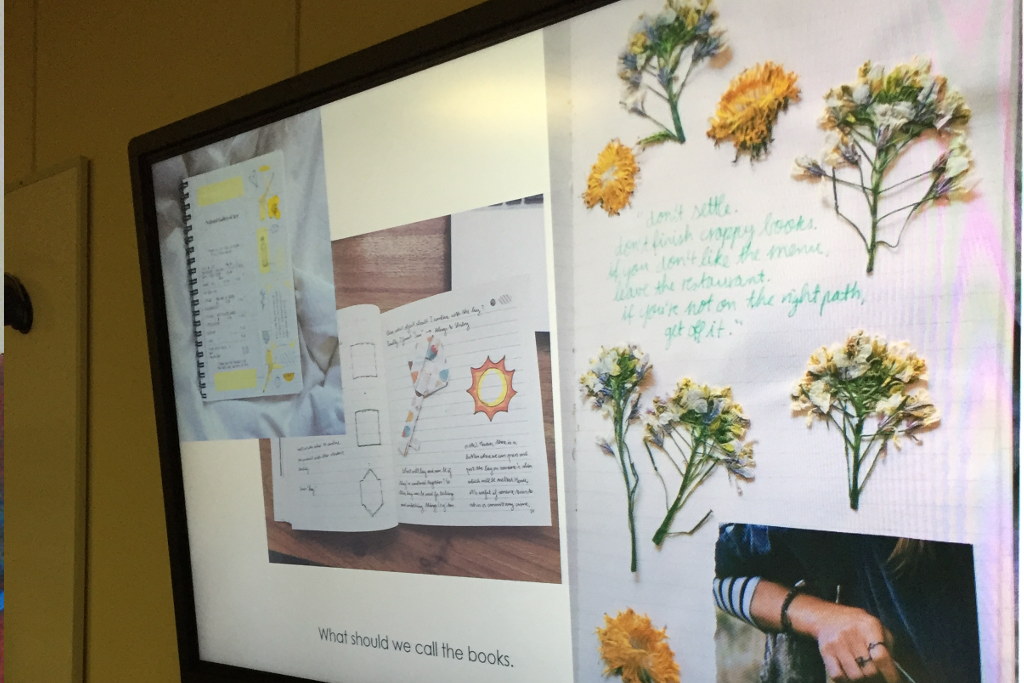

Documentation for and by children: When I see the responses of children who are looking at documentation of themselves at work, it is always exciting. Whether the documentation is one photo with some text, or a whole panel of work, the children always have something more to say. If they are seeing the documentation in its raw form (let’s say on a laptop), we can ‘check in’ with them and see if we are articulating their ideas and work accurately. They are happy to tell us when we have it wrong! When they themselves document what has happened, either through drawing, photography or writing, it is a validating experience, and one that we can take back to the whole group for futher discussion. In fact, many educators now begin their day with children by going back to documentation from the day before. Here is a way for young children to ‘hold in mind’ what their ideas were yesterday, and either change their minds or build upon what happened if they choose.

Documenting a journey: Whether the process was long or short, messy (in terms of directions taken and/or changed) or not, making the journey of learning visible is so valuable. As teachers, we can see all the tangents and where they led, the questions that children took up and explored, or ignored, the resources that were valuable to the children, how ideas changed over time or else solidified, and what we ourselves learned from the children and their process. When the children see this complex journey, what does it tell them about learning? Perhaps they will take from this visual narrative that learning is complex, puzzling, exciting, often messy, and not only how much they learned, but how they learned it.